Instructions: Please read the online module below. It will take you approximately 25 minutes to read.

Learning Objectives

By the end of this module, you will be able to:

- Identify plain language strategies to implement when writing key information

- Name formatting practices to enhance readability of key information

- Explain why assessing participant understanding and appreciation is important

- Describe available validated assessments

Introduction: Why Would You Want to Optimize Your Consent Process?

Informed consent is a cornerstone of the ethical conduct of research, and the duty to obtain informed consent is part of every major code of research ethics.1 Informed consent includes objective elements, specified in Federal Regulations, regarding the kinds of information that must be shared with potential participants. Informed consent also includes subjective elements such as a potential participant’s ability to understand and appreciate consent information.2

Informed consent is a cornerstone of the ethical conduct of research, and the duty to obtain informed consent is part of every major code of research ethics.1 Informed consent includes objective elements, specified in Federal Regulations, regarding the kinds of information that must be shared with potential participants. Informed consent also includes subjective elements such as a potential participant’s ability to understand and appreciate consent information.2

Evidence indicates that research participants frequently do not understand the information contained in consent forms.3-5 In addition, healthcare providers often overestimate participant comprehension of consent information.6

The National Institutes of Health (NIH) have made improving informed consent a high priority, and have spent more than $80 million dollars identifying effective consent practices.7 Recent revisions to the Federal Regulations for the Protections of Human Subjects (45CFR46), or Common Rule, provide increased opportunities for researchers to improve their consent processes.

In addition to meeting Federal Regulations, improving the consent process has several benefits. First, it enhances respect for persons and the ethical protections of research participants by ensuring participants have the necessary information to make a decision about whether to take part in research.8 Improved consent processes may also increase the efficiency of Institutional Review Board (IRB) review by reducing concerns about informed consent processes, which is the most common concern about research protocols voiced by IRB members.9 Improving informed consent processes may also reduce legal liability in some cases.

Older Adults and Cognitive Impairments

The NIH recently issued a policy requiring the inclusion of older adults (age 65+) in clinical trials unless there is a scientific or ethical reason not to include them.10 This policy is meant to address the frequent exclusion of many older adults from clinical research. Older adults are at increased risk of developing cognitive impairments, and this is one reason they have historically been excluded from research. A cognitive impairment is defined as “when a person has trouble remembering, learning new things, concentrating, or making decisions that affect their everyday life.”11

Cognitive impairments are a distinguishing feature of age-related neurological diseases like Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias.12 However, other common diseases associated with aging, such as diabetes and heart disease, are also associated with cognitive impairments.13,14 Therefore, it is important to remember that risk of cognitive impairments are not limited to particular groups of older adults – such as those with neurological or psychiatric conditions.

Consent processes need to accommodate older adults with, or who are at risk of developing, cognitive impairments rather than simply excluding them. Such participants require additional safeguards to ensure they can provide informed consent.15,16

Evidence-Informed Practices for Consent in Clinical Trials

Systematic reviews and expert consensus have identified multiple consent practices that researchers can use to improve their informed consent processes.4,7,17 Importantly, these practices have been tested and demonstrated to be effective in randomized clinical trials with cognitively impaired populations. These evidence-informed practices include:

- Using plain language and formatting to optimize readability. Consent forms are frequently long and complex documents. Participants prefer and achieve higher levels of understanding with consent forms that use plain language and are formatted to maximize readability.4,18-20 Required key information sections must be “organized and presented in a way that facilitates comprehension.”21

- Assessing understanding and appreciation of consent information. Using a validated assessment tool helps researchers achieve consistent and trustworthy ratings regarding comprehension of consent information.22 There are a number of validated assessment tools that can be used to assess a participant’s ability to understand consent information.

These evidence-informed practices are not routinely followed in clinical trials. The Consent Practices Project aims to raise awareness of these practices among clinical research coordinators. The remaining portions of this module provide further details on these evidence-informed practices.

Using Plain Language and Formatting to Optimize Readability

Introduction

The Federal Regulations for the Protections of Human Subjects (45CFR46), or Common Rule, require that informed consent documents begin with:

The Federal Regulations for the Protections of Human Subjects (45CFR46), or Common Rule, require that informed consent documents begin with:

“A concise and focused presentation of the key information that is most likely to assist a participant in understanding the reasons why they might or might not want to participate in research. This part of the information must be organized and presented in a way that facilitates comprehension.”21

This section will provide an overview of evidence-informed strategies that can improve understanding and readability of the newly required key information.

The Key Information Requirement

Consent forms are often overly long, complex, and contain technical jargon that makes them difficult to understand.3,4 They also frequently serve as legal documents to protect institutions, sponsors, and investigators from liability.26 Key information is meant to provide the most important information that a reasonable person would require to make a decision about whether to participate in research. Key information should not include the “pages of tables” or “hundreds of risks” that are commonly included in consent forms.23

According to the Secretary’s Advisory Committee on Human Research Protections (SACHRP) the new requirements for key information provide:

“An opportunity to fundamentally change and improve the consent process and the consent form in human subjects research. While the best solutions are not immediately apparent, the new requirements provide the regulatory mandate and the flexibility to test and implement substantial improvements. The process of writing consent forms and obtaining consent had become stagnant and overburdened with competing purposes, with most clinical consent forms following the order of the elements of consent as presented in the regulations.”24

Why Focus on Key Information?

Informed consent documents generally serve two purposes: provide information to participants about research and protect institutions and sponsors from liability.23 As a result, sponsors and IRBs may not permit changes to template consent forms that they provide. In contrast, the Federal Regulations require that key information is specifically designed to enhance understanding of the main reasons a person would or would not want to take part in research. The Federal regulations require that information be “organized and presented in a way that facilitates comprehension.” As a result, IRBs and Sponsors should provide more flexibility in making changes to key information documents that maximize comprehension.

Use Plain Language When Writing

Plain language is writing in a way that is clear, concise, and simple.25 Nearly half of US adults have low literacy.26 However, studies have found that consent templates at major medical schools had an average reading level 2 to 4 grades higher than the general US population.3 Using plain language is an evidence-informed communication practice that promotes understanding of information.27

Text Box 1 summarizes guidance provided by the Federal Plain Language Guidelines.28

Text Box 1. Using Plain Language

Choose simple words

- When writing key information, use simple words and phrases. Define technical terms, and avoid using jargon or words that need defining

- Avoid using acronyms and abbreviations

- Click HERE to visit a website created by the government that provides a list of commonly used complex words and suggested substitutes

- Click HERE to visit the CDC’s website that will help you translate technical or jargon into plain language

Keep sentences and paragraphs short

- Reducing the number of words in a sentence enhances readability and understanding of the information

- Sentences should be less than 20 words

- Paragraphs should be short and contain a single idea

Write in the active voice

- Writing using the active voice more clearly conveys to participants what they will have to do as part of the study. Using the active voice makes it clear who is supposed to do what. For example:

- You must take medication 3 times a day = ACTIVE VOICE

- Medication must be taken 3 times a day = PASSIVE VOICE

Additional tips

- Less is more! Only provide the most pertinent information that the participant needs to determine whether they want to participate

- Include “you”, “we”, and other pronouns to keep the tone friendly and personal

- Use the same terms consistently. For example, if you use the word “research” use this term consistently rather than switching between research, clinical trial, and project

You can download the Federal plain language guidelines here: https://www.plainlanguage.gov/guidelines/

Formatting Documents to Maximize Readability

The way a document is formatted has a major impact on how its content is understood by readers.17 Dense and cluttered text deters readers and can prevent comprehension of the material.

Consent forms often contain dense text, small font, and do not have headings to guide readers through the material. This leaves no way for readers to scan the information and quickly find what they are looking for. Documents with dense text contain very little white space. White space refers to areas of the document that do not contain text.

Formatting key information using evidence-informed practices can improve the reader’s understanding of the information.

Text Box 2 summarizes guidance on formatting to maximize readability provided by the Federal Plain Language Guidelines.28

Text Box 2. Formatting to Maximize Readability

Increase white space

- Use 1-inch margins throughout the document

- Use easy to read fonts

- Font size should be a minimum of 12 point

Create lists and tables

- Creating a list can help break up dense paragraphs of text

- Consent documents often contain long dense paragraphs, for instance describing the risks of a study. Instead of writing the risks of a study in a long paragraph, you can create a bulleted list of the major risks or use a table to describe risks

- Tables and lists should be short and should not be used as an opportunity to cram in extra information

Use headings and text boxes

- Headings can make it easier to find information and guide the reader to relevant topics

- Set headings in bold

- Leave space before and after headings

- Headings should be 1 font sizer larger than body text

- Text boxes can be used to highlight important information

Additional tips

- Visual aids are another way to convey information, but make sure you seek feedback on the visual aid to make sure it’s clear and culturally appropriate

- When formatting your key information, avoid using all CAPITAL LETTERS, italics, and underlining. Instead, use bold for emphasis

- Use ragged right margins

Formatting key information in the ways described may lead to a document that is longer than the original, but it will be easier to read and more easily understood. On the other hand, incorporating plain language may actually reduce the length, producing a document that is shorter and easier to read for participants.

Summary

Revisions to the Federal Regulations require that informed consent documents begin with a “concise and focused presentation” of the key information a participant requires prior to enrollment. Individuals frequently do not understand consent information, and the required key information is an opportunity to ameliorate consent comprehension. Evidence-informed strategies such as using plain language and formatting documents to maximize readability can improve participants’ ability to comprehend information.

Assessing Understanding and Appreciation of Consent Information

Introduction

A fundamental right of research participants is to make informed decisions that align with their personal preferences.1 However, research participants often fail to understand consent information due to a variety of factors. Using a validated instrument to assess participants’ understanding of consent information, in appropriate contexts, can help ensure participants are informed prior to deciding whether to participate in research.

A fundamental right of research participants is to make informed decisions that align with their personal preferences.1 However, research participants often fail to understand consent information due to a variety of factors. Using a validated instrument to assess participants’ understanding of consent information, in appropriate contexts, can help ensure participants are informed prior to deciding whether to participate in research.

This section will provide an overview of:

- The benefits of assessing understanding and appreciation

- Validated assessment tools and their characteristics

- What to do with assessment results

Understanding and Appreciation

The Federal Regulations for the Protection of Human Subjects (45 CFR 46) stipulate that individuals have adequate information and time before deciding whether to take part in research:

“Informed consent as a whole must present information in sufficient detail relating to the research, and must be organized and presented in a way that does not merely provide lists of isolated facts, but rather facilitates the prospective subject’s or legally authorized representative’s understanding of the reasons why one might or might not want to participate.”21

The Federal Regulations also require additional safeguards when research participants are at risk of impaired decision making:

“When some or all of the subjects are likely to be vulnerable to coercion or undue influence, such as children, prisoners, individuals with impaired decision-making capacity, or economically or educationally disadvantaged persons, additional safeguards [must be] included in the study to protect the rights and welfare of these subjects.”21

In order to make informed decisions, participants must achieve both understanding and appreciation of consent information.2- Understanding is the ability to comprehend the meaning of information.2

- Appreciation is the ability to recognize how facts are relevant to oneself.2 Appreciation also involves believing the information is true.

Why Do People Fail to Understand Consent Information?

People may fail to understand and appreciate consent information for a variety of reasons. For example, they may have a cognitive impairment caused by neurological, psychiatric, or other medical diagnoses.29 Data has also shown that people who are very young or very old often have difficulties understanding information.30 Understanding and appreciation may also be compromised if information is presented in an unclear manner, such as using language that is highly technical or legal.

Additional reasons that participants may not understand or appreciate consent information are:30,31

- Having limited English proficiency

- Perceiving the information as threatening

- Simply not believing the person providing information

- Feeling overwhelmed with information, such as a new diagnosis

An individual’s ability to understand information can change from one day to the next.

When Should I Assess Participants’ Understanding and Appreciation?

Researchers should assess participants’ understanding and appreciation of consent information when the risks of a study are great enough to justify determining whether people truly understand the information before making a decision to take part.32 Generally, these are studies that involve greater than minimal risk. As the risk level of a study increases so will the need to include assessments of understanding and appreciation. When it is determined that the risks of a study warrant assessing capacity, every participant should be assessed on their understanding and appreciation of consent information.

This approach has several advantages:

- Ensures that everybody understands and appreciates the research they are participating in, which prevents researchers from wrongly assuming that participants understand the information that was presented to them.

- Helps identify participants who may require additional education or clarification about the research.

- Helps identify weaknesses in the consent process. For example, if many participants misunderstand the same piece of information, perhaps the consent process needs to be modified.

Screening all participants—rather than just certain individuals—also avoids unfairly stigmatizing those with diagnostic labels, such as schizophrenia or dementia, by presuming their capacity is diminished. This also ensures that participants who are undiagnosed are not missed. In situations where a legally authorized representative (LAR) is providing consent for a participant, it may be appropriate to assess their understanding before obtaining informed consent.

Validated Assessments

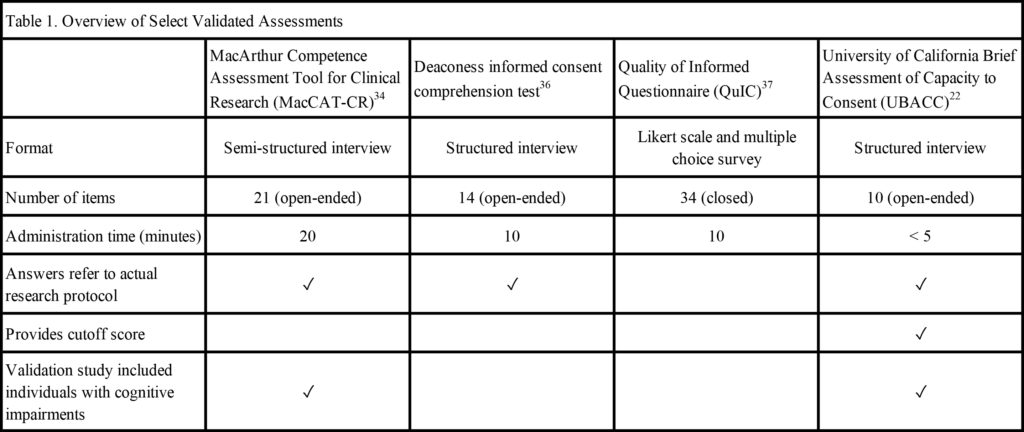

Table 1 below provides an overview of some validated assessments of participant understanding of consent information. All the assessments in Table 1 have published validation papers supporting them. There are additional validated assessments available that you might consider using. Dunn and colleagues identified 10 validated assessments that could be used to determine understanding of consent information.32

Assessments May Not Always Be Appropriate

There are circumstances when it may not be appropriate to assess every participant. When conducting a minimal risk study, such as a one-time survey, it may be unnecessarily burdensome. In situations where you already know the participant population will do very poorly on assessments—for example, if they are in the later stages of Alzheimer’s disease—it is also reasonable to skip an assessment of understanding because it may cause unnecessary frustration or embarrassment for the participant. In these cases, assessing understanding for a surrogate or Legally Authorized Representative may be more appropriate.

What to Do With Assessment Results

If assessment results indicate that an individual lacks understanding of consent information, this could be due to many factors described above in “Why do People Fail to Understand Consent Information.” When scores are low following an assessment, it is important to first determine whether the potential participant is capable of understanding the consent information by asking the following questions:

- What is causing the lack of understanding?

- Could the specific information that the participant misunderstood be explained or presented in a better way?

It is necessary to use clinical judgement regarding whether to discuss misunderstood information with a participant if scores are low after assessment.

Discussing Misunderstood Information

- Try to obtain informed consent on another day (if you think their cognitive abilities fluctuate).

- Ask the participant to appoint a surrogate decision maker or identify a Legally Authorized Representative (LAR). It is appropriate to assess the LARs’ understanding of consent information for studies that are greater than minimal risk.

- Exclude the participant from participation in the study. It may feel difficult to exclude a participant from research. The participant might feel disappointed or you might feel pressure to recruit individuals. However, it does not respect patient autonomy, or satisfy Federal research regulations, to enroll participants who do not understand the research.

Summary

Ensuring that research participants understand consent information respects participant autonomy. Using a validated assessment in appropriate circumstances can help determine if participants understand consent information prior to enrollment. Assessing all individuals when the risk level of a study justifies it can ensure no individuals are missed and avoids unfairly stigmatizing certain groups. When participant scores on a validated assessment are low, there are options available for researchers such as educating, consenting on a different day, appointing a Legally Authorized Representative (LAR), or excluding an individual from participation.

Disclaimer

The information in this module is not legal advice and may not pertain to your individual situation or state laws.

This online module was developed by Jessica Mozersky, Erin D. Solomon, and James M. DuBois at the Bioethics Research Center at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis with funding from the National Institutes of Aging [R01 AG058254-01, NIA].

Next steps: Now that you have read the module in full, go back to the browser window that contains the Qualtrics survey. Complete the rest of the survey.

If you accidentally closed that browser window, click on the link we sent to you in the initial email and you should return to the same point in the survey.

References

- Emanuel EJ, Wendler D, Grady C. What makes clinical research ethical? JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association. 2000;283(20):2701-2711.

- Grisso T, Appelbaum PS. Assessing Competence to Consent to Treatment: A Guide for Physicians and Other Health Professionals. New York: Oxford University Press; 1998.

- Paasche-Orlow MK, Brancati FL, Taylor HA, Jain S, Pandit A, Wolf M. Readability of consent form templates: A second look. Irb. 2013;35(4):12-19.

- Flory J, Emanuel EJ. Interventions to Improve Research Participants’ Understanding in Informed Consent for Research: A Systematic Review. JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association. 2004;292(13):1593-1601.

- Resnik DB. Do informed consent documents matter? Contemp Clin Trials. 2009;30(2):114-115.

- Montalvo W, Larson E. Participant Comprehension of Research for Which They Volunteer: A Systematic Review. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2014;46(6):423-431.

- Dubois JM, Bante H, Hadley WB. Ethics in Psychiatric Research: A Review of 25 Years of NIH-funded Empirical Research Projects. AJOB primary research. 2011;2(4):5-17.

- National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research. The Belmont report: Ethical principles and guidelines for the protection of human subjects of research. Washington, D.C.: United States Department of Health, Education, and Welfare; April 18, 1979.

- Stark L. Behind closed doors: IRBs and the making of ethical research. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 2012.

- National Institutes of Health. Inclusion Across the Lifespan Policy. In:2019.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Cognitive impairment: A call for action, now! Atlanta, GA: CDC; February 2011.

- Palmer BW, Ryan KA, Kim HM, Karlawish JH, Appelbaum PS, Kim SY. Neuropsychological correlates of capacity determinations in Alzheimer disease: implications for assessment. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2013;21(4):373-381.

- Sinclair AJ, Girling AJ, Bayer AJ. Cognitive dysfunction in older subjects with diabetes mellitus: impact on diabetes self-management and use of care services. Diabetes Research and Clinical Practice f. 2000;50:203-212.

- Vogels RLC, Scheltens P, Schroeder-Tanka JM, Weinstein HC. Cognitive impairment in heart failure: A systematic review of the literature. European Journal of Heart Failure. 2007;9:440–449.

- Taylor JS, DeMers SM, Vig EK, Borson S. The disappearing subject: exclusion of people with cognitive impairment and dementia from geriatrics research. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60(3):413-419.

- Herrera AP, Snipes SA, King DW, Torres-Vigil I, Goldberg DS, Weinberg AD. Disparate inclusion of older adults in clinical trials: priorities and opportunities for policy and practice change. Am J Public Health. 2010;100 Suppl 1:S105-112.

- Nishimura A, Carey J, Erwin PJ, Tilburt JC, Murad MH, McCormick JB. Improving Understanding in the Research Informed Consent Process: A Systematic Review of 54 Interventions Tested in Randomized Control Trials. BMC medical ethics. 2013;14:28.

- Kim EJ, Kim SH. Simplification improves understanding of informed consent information in clinical trials regardless of health literacy level. Clinical trials. 2015;12(3):232-236.

- Agre P, Campbell FA, Goldman BD, et al. Improving Informed Consent: The Medium is Not the Message. IRB: Ethics & Human Research. 2003;Suppl 25(5):S11-S19.

- Campbell FA, Goldman BD, Boccia ML, Skinner M. The effect of format modifications and reading comprehension on recall of informed consent information by low-income parents: a comparison of print, video, and computer-based presentations. Patient Education and Counseling. 2004;53(2):205-216.

- Subpart A of 45 CFR 46: Basic HHS Policy for Protection of Human Subjects (As revised on January 19, 2017, and amended on January 22, 2018 and June 19, 2018). In: US Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Health, Office for Human Research Protections, eds 2018.

- Jeste DV, Palmer BW, Appelbaum PS, et al. A New Brief Instrument for Assessing Decisional Capacity for Clinical Research. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2007;64(8):966-974.

- Menikoff J, Kaneshiro J, Pritchard I. The Common Rule, Updated. New England Journal of Medicine. 2017;376(7):613-615.

- New “Key Information” Informed Consent Requirements. In: The Secretary’s Advisory Committee on Human Research Protections, ed. Attachment C2018.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Health Literacy. https://www.cdc.gov/healthliteracy/developmaterials/plainlanguage.html.

- Mark Kutner EG, Justin Baer. National Assessment of Adult Literacy (NAAL). National Center for Education Statistics;2005.

- The Plain Language Action and Information Network. Plain Language. 2019; https://www.plainlanguage.gov/.

- Government US. Federal Plain Language Guidelines. https://www.plainlanguage.gov/guidelines/.

- Alzheimer’s Association. Research consent for cognitively impaired adults. Alzheimer Disease and Associated Disorders. 2004;18(3):171-175.

- Barstow C, Shahan B, Roberts M. Evaluating Medical Decision-Making Capacity in Practice. Am Fam Physician. 2018;98(1):40-46.

- Appelbaum PS, Grisso T. MacCAT-CR: MacArthur Competence Assessment Tool for Clinical Research. Sarasota, FL: Professional Resource Press; 2001.

- Dunn LB, Nowrangi MA, Palmer BW, Jeste DV, Saks ER. Assessing Decisional Capacity for Clinical Research or Treatment: A Review of Instruments. The American journal of psychiatry. 2006;163(8):1323-1334.